Do you think journalists should be compelled to quote women as often as they quote men? The proposition sounded a bit radical, even to me, back in 2014 when Edelman CEO Lisa Kimmel invited me to defend it in a public debate.

Seven years on, it’s no longer a radical idea. Journalists and newsrooms across this country and around the world are now actively monitoring the sources they interview and the guests they feature in a bid to better reflect the realities of the populations they serve.

Last week with the help of media strategist and co-founder of Canadian Journalists of Colour, Anita Li, we launched #DiversifyYourSources — a campaign to encourage members of Canada’s news media to publicly pledge to track the gender of their sources to bridge the current, lamentable gap. And we’ve created a simple downloadable spreadsheet that makes it easy for them to monitor other dimensions of diversity, too.

Many individual reporters have signed up, and more than a dozen editors-in-chief pledged on behalf of their entire newsrooms. These included Irene Gentle at the Toronto Star, Andrew Yates at HuffPost, and Steve Bartlett of Saltwater Press.

Said Bartlett, “Media outlets must do a better job of reflecting the audiences and communities they serve. That cannot happen without diversifying the voices in their coverage. Our newsrooms are committing to do this. As a result, they’ll make an even greater difference by engaging and informing more people.”

The Toronto Star’s Irene Gentle cited “better journalism and a better society” when declaring her paper’s commitment to measuring, which predates our campaign. As her colleague, senior editor Julie Carl, noted, “We already embrace this principle, but it is always good to say these things out loud and proud.”

Those who have pledged work in a wide variety of news formats, from online sites and multi-platform magazines to TV newsrooms and wire services. They include publishers and political correspondents, radio hosts and columnists.

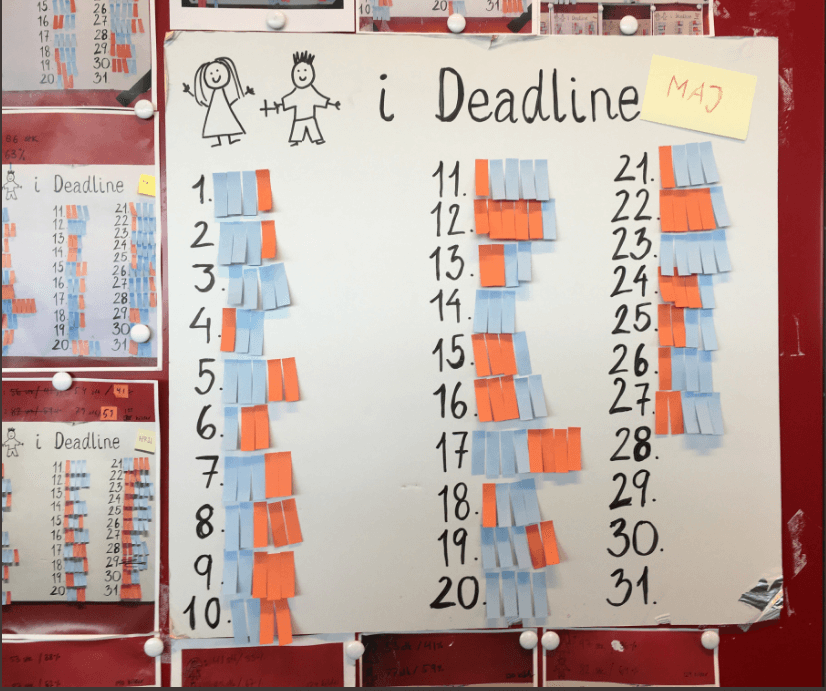

In the context of perpetual deadlines and dwindling resources, time-strapped reporters and producers aren’t really looking to add to their to-do list. And as CBC radio host Duncan McCue notes, there’s no denying that “Diversifying your sources takes more time.” He acknowledges that “It’s not easy building relationships with vulnerable groups who have been historically left out of media. But hard work pays off, resulting in richer journalism and broader audiences.”

Our #DiversifyYourSources campaign doesn’t require those who pledge to commit to meeting a 50:50 ratio — though having news reporting and programming in all media reflect gender parity is our ultimate goal. But the tracking commitment is predicated on the recognition that “what gets measured gets done.”

We know that for journalists who see their work as fundamental to the maintenance of democracy, discovering from their own data that they’re seeking insight and context primarily from a small subsection of the population tends to inspire a change in practice. Adrienne Lafrance and Ed Yong of The Atlantic have both written about their experiences on this front.

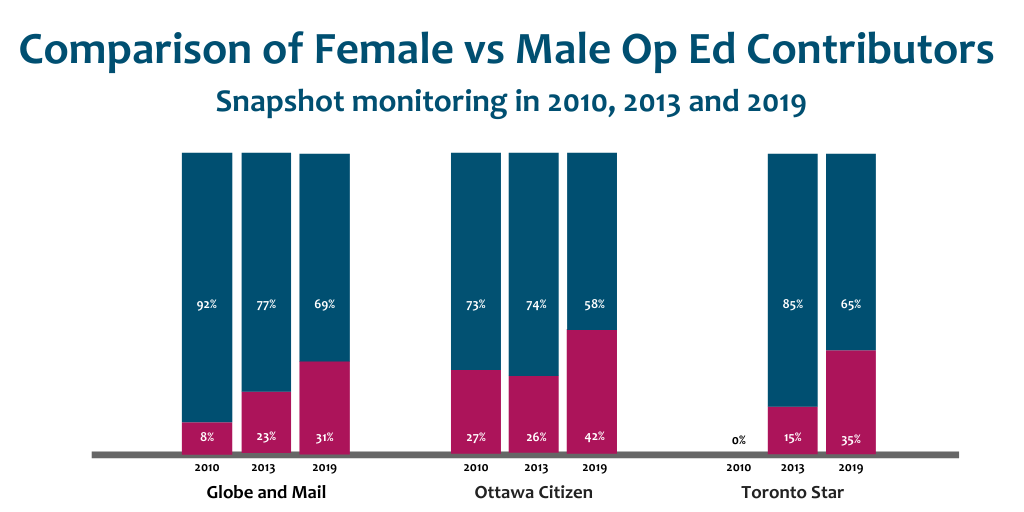

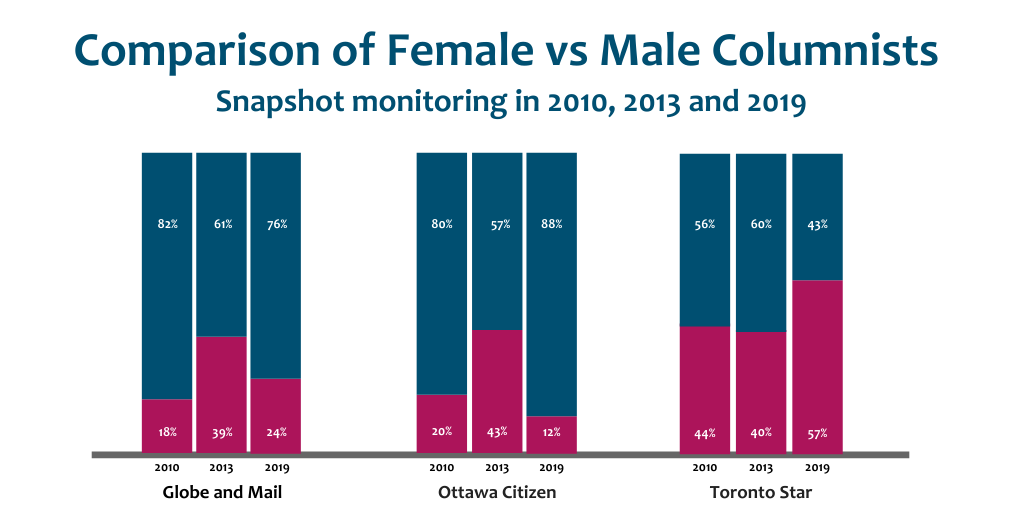

Meanwhile, a number of Canadian media organizations, large and small, have been quietly monitoring, improving and sharing their numbers for some time.

A few years ago we publicly recognized the team behind TVO’s The Agenda for their explicit commitment to featuring as many women guests as men. And Scott White, the Editor-in-Chief of The Conversation and a board member of Informed Opinions has also led his colleagues in tracking their numbers to achieve equitable representation.

“Calling all Canadian journalists: Join @Scott_White, editor-in-chief of @ConversationCA, and #DiversifyYourSources!

It takes less than 60 seconds to make this crucial commitment. Sign up and share today: https://t.co/zSRaF8qE1l #cdnmedia pic.twitter.com/L9aivmynO5

— Informed Opinions (@InformedOps) February 8, 2021“

In her pledge, Jennifer Ditchburn, Editor-in-Chief of Policy Options, who also serves on our board, said that 46.7% of authors contributing to her publication last year were women. Moreover, she noted, “We are also working to ensure our magazine reflects the overall diversity of Canadian society.”

The coronavirus pandemic has likely helped increase many people’s appreciation of why these commitments are important. Many studies and news reports have pointed out the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on women — especially Black, Indigenous, and immigrant women, as well as those living in poverty, or with a disability, or with an abuser.

How can you cover a global virus that has put hospital nurses, grocery store check-out clerks and long-term care home support workers on the front lines of the battle if you’re only interviewing men?

In fact, the over-representation of women in public health and the exceptional communication skills of Drs. Teresa Tam, Deena Hinshaw and Bonnie Henry have contributed to the increased amount of air time women sources have gotten over the past six months. The shut-down or curtailment of many professional sports leagues has also led to a corresponding dip in coverage that typically quotes women a paltry 4% of the time.

But what happens when the pandemic ends?

Informed Opinions’ goal is to encourage consciousness now so that in the months ahead, the monitoring habit and resulting behaviour shift cements a new normal.

As I wrote in a piece published earlier this week by Policy Options,

Journalists regularly cite as inspiration for their work the goal of “afflicting the comfortable and comforting the afflicted.” Doing that requires much more attention to who’s being quoted, and measurement is necessary. So as part of our pledge campaign, we’ve created an electronic spreadsheet to facilitate the kind of self-monitoring that science journalist Ed Yong calls “a vaccine against self-delusion.”

“This pandemic demands both kinds of vaccines. And our aim in encouraging journalists to embrace the responsibility they have to reflect the realities of all the citizens they serve, is a better, safer, more equitable world for all. “

We all have a stake in that.