I’m embarrassed to confess how long it’s taken me to wake up to this revelation.

I ask women every day to step out of their comfort zones and speak up about things they know to be important — to share their insights, challenge ignorance, and make change. But recently it occurred to me that I have been unwilling to step outside my own comfort zone.

I speak up all the time in my advocacy work. But I’ve been doing that for 30 years; it’s easy for me. What’s not easy for me is asking other people to help fund that work. And so mostly I haven’t.

Since founding Informed Opinions ten years ago, I’ve asked three established feminist philanthropists for contributions to our work, and been so gratified by their support. And as Christmas approaches every year, we’ve pulled together an email or two inviting people on our contacts list to make us part of their end-of-the-year giving plans. Many have, and we so value their donations.

But these efforts have always made me enormously uncomfortable. As a result, I’ve focused almost all of my revenue-generating efforts on developing, promoting and delivering our programming.

Over the past decade, we’ve essentially leveraged the few government and foundation grants we’ve received to build a social enterprise. We’ve cultivated relationships with universities and non-profits, and created a suite of practical workshops that help executives, scholars and advocates draw attention to the issues they know and care about. In the process, we’ve generated close to a million dollars in fee-for-service revenues. Those funds have been crucial to the impact we’ve had. They’ve supported our online resources and the ongoing expansion and promotion of our database of experts. I’m enormously proud of that.

But the diligent members of my board have done the math that I’ve been avoiding. They’ve pointed out that just because Samantha and I are willing to work long hours for considerably less than market value because we “love the work and are committed to the mission” (and yes, I DO appreciate that this is one of the many ways women keep ourselves small and undervalued), doesn’t mean that doing so is a defensible position or recipe for sustainability.

So this year I am focusing my attention on leveraging both our demonstrated impact and the unique cultural moment we’re in. I am actively seeking the resources necessary to scale up our work and deliver on our promise.

I’m often in rooms full of smart, knowledgeable and articulate women. Invariably some of them express reluctance about having a public voice, knowing that it may open them up to criticism. I understand that. But here’s what I ask them:

“Do you believe the work you do is important? That it’s getting the attention it deserves? That it’s worthy of support?”

And then I remind them that if, despite their knowledge and commitment, they’re not willing to speak up, perhaps no one will. And all the research, insight and brilliance in the world is only valuable when it’s shared.

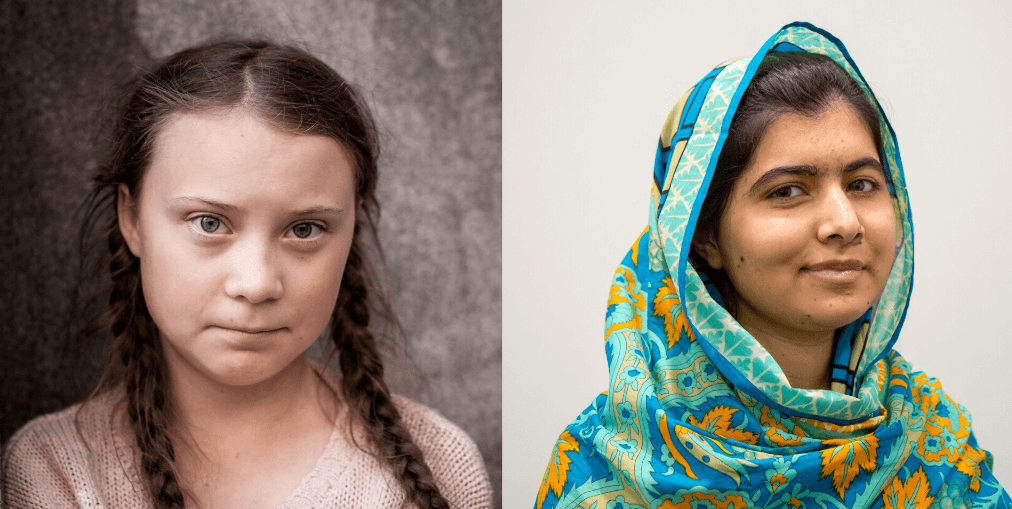

Malala Yousafzai and Greta Thunberg have made the world stand up and take notice of the causes they champion as teenagers. And as a result of speaking up, they’ve been shot in the head or publicly condemned by the President of the United States. But that hasn’t stopped them.

Founder of the Op Ed Project, Katie Orenstein, also acknowledges that speaking up has consequences. But she points out that the alternative is to be inconsequential. Failing to capitalize on the potential we have to make a difference is likely to keep us on the wrong end of the consequential-inconsequential continuum.

Last fall, I asked Barbara Grantham, then President of the Vancouver Hospital Foundation and now incoming CEO of Care Canada and a member of Informed Opinions’ advisory committee member, for fundraising advice. Among her many insights was this:

“Philanthropy is an opportunity for people to be their best selves.”

Even though my own giving capacity is limited, I understand that. When I donate to a food bank or woman’s shelter, I feel an expanded sense of my own humanity. And now I’m working to embrace the capacity Informed Opinions has to offer others a similar experience.

We’re collaborating with a wonderful team of women at capitalW, an initiative launched last year by Kathryn Babcock. When I first met Kathryn to explore whether or not we might work together to raise funds for Informed Opinions, almost the first sentence out of her mouth was:

“I’m fascinated by money.”

I was genuinely shocked by this admission. I’ve been an advocate for 30 years, saw her as a sister in the trenches, and was still deep into my denial of the centrality of resources to make change happen. I’d spent years taking pride in my relentless focus on the work, not the infrastructure; I regularly told others I wasn’t looking to build an empire, I just wanted to make change. And that meant, in my naive and unquestioning mind, not thinking about money. So to hear a fierce feminist flat-out confess to being preoccupied by it was startling.

But Kathryn’s sophisticated analysis of the flow of money in a capitalistic society and vision of how we should be leveraging the untapped potential of women’s consumer spending for equality challenged me to think differently about my own relationship with money. Within moments of meeting her, I found myself saying, “What can I do to help you?”

So six months later, Informed Opinions has embarked on a concerted campaign to scale up the critically important and potentially far-reaching work we’re doing. I’m still often deeply uncomfortable speaking the words, “Would you consider making a contribution…” But in doing so, I feel a new connection to the women who email us every week or so to say something like:

“A journalist called wanting me to comment on national TV and I was going to say ‘no, I’m not the best person’, but I heard your voice in my head and so I said yes. I did the interview — without throwing up! — and I’ve had great feedback. Thank you so much!”

If you’re already donating to Informed Opinions, I thank you from the bottom of my heart. If you’re not, but want to know more about the impact we’ve had, what we’re aiming to do next, and how you or your organization or network can help, click here.